Unlocking Plant Growth: Scientists Discover How Cell Walls Guide Stem Cells

Imagine if our bodies could grow new organs throughout our entire lives. Plants do this constantly, thanks to tiny, powerful reservoirs of stem cells. But how do these cells know when to divide, and how do they ensure each division is perfectly oriented to build a leaf, a stem, or a flower? New research reveals that the answer lies not just within the cells, but in the very walls that surround them. A team of scientists has discovered a hidden “molecular gatekeeper” that controls the stiffness of these walls, directly guiding the fate of plant stem cells.

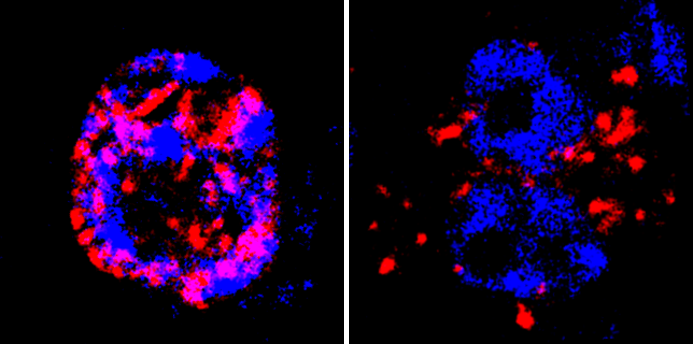

Left: the shoot apex of an Arabidopsis thaliana plant. Right: the shoot apical meristem. Actively dividing stem cells are shown in green, and the cell walls are labelled in magenta.

The Discovery: A Tale of Two Walls

All plant cells are encapsuled in a wall, a rigid yet dynamic structure long thought to be a simple scaffold. The new study, led by Dr. Weibing Yang at the CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Plant Sciences and published in Science, shows this wall is anything but static. Inside the stem cell hub—the shoot apical meristem—the researchers found a surprising "bimodal" pattern.

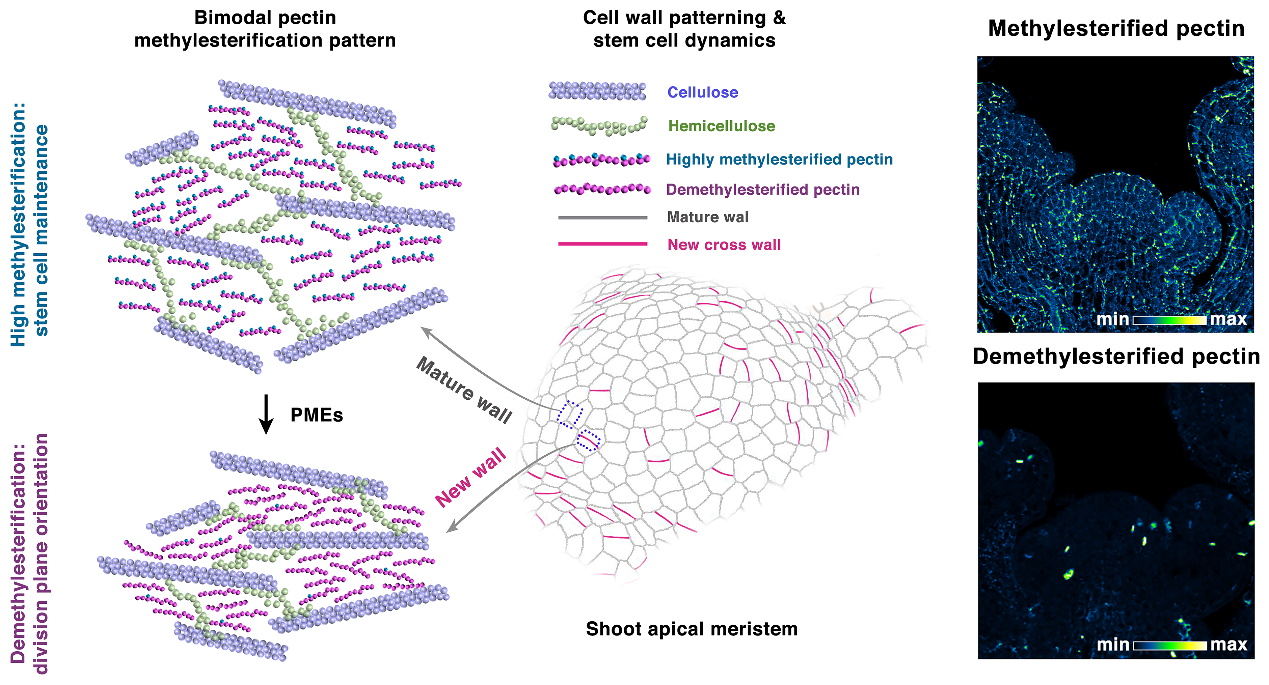

Think of it like this: the old, mature walls are “stiff”, acting like the load-bearing beams of a building. Meanwhile, every time a cell divides to create two new cells, the new wall that forms between them is initially “soft” and flexible. This difference in stiffness is controlled by a simple chemical tweak to a gel-like component in the wall called pectin. Stiff walls have highly “methylesterified” pectin, while soft, new walls have “de-methylesterified” pectin.

A "bimodal" pectin modification pattern in plant stem cells.

The Molecular Gatekeeper

This precise pattern begged the question: how does the plant ensure the “softening” enzyme only works on new walls and doesn't accidentally weaken the old, crucial ones?

The team pinpointed a key enzyme gene called PME5, the master switch that softens pectin. But they found a clever trick: the cell keeps the instruction manual for this enzyme—the PME5 messenger RNA (mRNA)—under lock and key inside the nucleus. It is like having a powerful tool stored safely in a toolbox.

Only when a cell is actively dividing does the “toolbox” open. As the nucleus temporarily disassembles, the PME5 mRNA is released. It is immediately translated into the PME5 enzyme, which is delivered right to the site of the new, forming wall, softening it precisely where and when it is needed. This ensures the mature walls remain stiff and structural, while new division walls are flexible enough to be positioned correctly.

When the Gatekeeper Fails

To prove this mechanism’s importance, the researchers disrupted it. When they genetically engineered plants to let the PME5 mRNA escape the nucleus prematurely, the softening enzyme was produced at the wrong time and place. This caused chaos: cell division patterns became disorganized, stem cell activity plummeted, and the plants grew stunted and produced strange, clustered fruits. This confirmed that the precise control of wall stiffness is not just a detail—it is essential for healthy plant development.

The authors of the paper: Xianmiao Zhu (left), Weibing Yang (middle), and Xing Chen (right).

Widespread and Promising Implications

This “nuclear sequestration” mechanism is a sophisticated form of gene regulation. The study also found it is not unique to PME5 but is used by several related enzymes, suggesting it is a common strategy. Furthermore, this bimodal wall pattern was found in diverse crops like corn, soybean, and tomato, indicating it is a conserved, fundamental principle of plant growth.

This discovery opens exciting new avenues for agriculture. Key crop traits—like the number of tillers, the length of the panicles, and the number of seeds—are all determined by stem cell activity. By learning this cell wall code, scientists could one day engineer crops with improved architecture and higher yields, all by tweaking the very walls that hold them up.

Article Link: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ady4102

Contact: http://wbyang@cemps.ac.cn